W swoich wypowiedziach podkreślał Pan wielokrotnie, że architektura oderwała się od użyteczności i sens istnienia budynków coraz częściej sprowadza się do ich wartości inwestycyjnej, ponieważ nieruchomości stanowią jeden z najważniejszych aktywów światowej gospodarki. Jak w kontekście zmian klimatu pogodzić to z faktem, że obiekty architektoniczne odpowiadają za 38 procent ogólnej emisji gazów cieplarnianych produkowanych przez człowieka?

To nie architektura jest odpowiedzialna za emisję, ale ludzie. Bo to w budynkach spędzamy większość czasu.

Ale czy architektura może nam pomóc zaadaptować się do zmian klimatu zamiast pogarszać sprawę?

To część większego problemu. Po pierwsze, każdy sukces osiągany jest kosztem czegoś lub kogoś innego. Ślad węglowy niektórych krajów jest pięć, dziesięć, sto razy większy w relacji do ich powierzchni. Zbyt opornie idzie nam przyznanie, że oznacza to czyjś upadek lub ograniczenie czyichś możliwości. Warto zwrócić uwagę, że pojęcie zrównoważonego rozwoju (sustainability) powstało w momencie, w którym świat pod względem gospodarczym zaczął stanowić jedną całość. Po raz pierwszy w historii można było operować sumą zerową z plusami po jednej i minusami po drugiej stronie. Wcześniej obie strony równania były zawsze rozdzielone, plusy nigdy nie mogły zrównoważyć minusów. To samo dotyczy architektury. Dlatego, moim zdaniem, trzeba o niej rozmawiać nie w kategoriach winy, ale w kontekście większego, bardziej złożonego cyklu, którego ona jest tylko elementem.

Skoro mowa o cyklach, część Pana badań dotyczy architektury efemerycznej. Na czym polega jej fenomen?

Im dłużej budynki istnieją, tym bardziej traktujemy je jak nieodzowne, oderwane od wszystkiego pomniki. Im żyją krócej, tym bardziej jesteśmy zmuszeni widzieć je jako elementy pewnego procesu. Jeżeli planując budowę jakiegoś obiektu, planuje się również jego rozbiórkę, koniec jest ważniejszy niż początek. Unicestwienie staje się ważniejsze niż kreacja.

Brevitas, flexibilitas, humilitas – krótkotrwałość, elastyczność i pokora – zamiast firmitas, utilitas, venustas – trwałości, użyteczności i piękna?

W rzeczy samej. W trwałości i rozwoju zrównoważonym w ogóle nie chodzi o wieczność. Planowanie zrównoważone polega na planowaniu tego jak odejść, gdy przyjdzie na to czas. W tym kontekście budynki w ogóle nie są interesujące. Im dłużej praktykuję architekturę, tym mniej interesują mnie budynki jako takie, jako wyabstrahowane arcydzieła. Ważniejsza jest rola jaką odgrywają w ogólnym systemie. Są częścią postprzemysłowego społeczeństwa, które produkuje i konsumuje oraz wypracowało pewne mechanizmy produkcji.

Przy okazji projektu nowego ratusza w Rotterdamie to właśnie strategia rozbiórki zapewniła wam bardzo korzystny wynik w certyfikacji BREEAM.

To był akurat czysty przypadek. Projekt miał wyjątkowo ograniczony budżet. Nie chcieliśmy oszczędzać na jakości, więc postanowiliśmy ciąć koszty realizacji. W Holandii zapłata za roboczogodziny przewyższa ceny materiałów budowlanych. Zaprojektowaliśmy więc budynek prefabrykowany, którego realizacja trwałaby bardzo krótko. Przy okazji mogliśmy pozwolić sobie na duże przestrzenie, daleko wysunięte wsporniki, bogatą fasadę, zewnętrzne tarasy, etc. Wszystko dzięki prefabrykacji. Okazało się przy tym, że obiekt, który łatwo się buduje, można równie łatwo rozebrać. Za to ostatnie dostaliśmy największego plusa na całej liście BREEAM. To trochę tak jakby prawdziwa odporność albo prawdziwa trwałość i zrównoważenie polegały na tym, żeby w ogóle nic nie budować.

Która z koncepcji – trwałość i zrównoważenie (sustainability) czy odporność (resilience) jest Panu bliższa?

Ani jedna, ani druga. Każde zbyt często używane słowo staje się bezużyteczną kalką. Gdybym musiał wybierać, wybrałbym zrównoważenie, ale jednego i drugiego staram się unikać.

Ale czy to nie odporność jest z definicji bardziej elastyczna, mniej nastawiona na trwałość i trwanie?

Jednak równocześnie jest też nastawiona na istnienie na przekór wszystkiemu, nieważne, jakim kosztem. Mam problem z tymi wielkimi słowami, odpornością, trwałością, itd. Mówią ci, co masz robić, ale nic nie obiecują w zamian. Są zbyt religijne – zbyt protestanckie, zbyt katolickie, za mało naukowe i nie dość ateistyczne.

Czy jest jakieś wielkie, modne słowo, którego Pan nie unika?

Zdolność przystosowania (adaptability). Wydaje mi się najmniej obraźliwe.

A co sądzi Pan o słowie „współdzielenie” (sharing) i takich pomysłach, jak pawilon zbudowany w trakcie Dutch Design Week 2017 z pożyczonych w okolicy materiałów?

Świetna i urocza inicjatywa, ale nie zapominajmy o skali problemu, o którym mówimy! To jakby sąsiad przyszedł pomóc nam gasić pożar niosąc ze sobą czajnik wody. Chociaż intencje są dobre, musimy rozróżniać pomiędzy tym, co dobre w sensie moralnym i tym, co skuteczne. Rzadko te rzeczy są ze sobą tożsame.

Woli Pan rozwiązania skuteczne?

Mam problem z każdą dyskusją nadmiernie przesyconą moralizmem, a cała debata wokół projektowania trwałego i spora część tej dotyczącej projektowania odpornego, jest dość moralistyczna. W Holandii intensywnie promowane są samochody elektryczne jednak rząd, lansując je jako zeroemisyjne, w celu dostarczenia energii do ładowania ich baterii buduje elektrownie węglowe, ponieważ są one tańsze. Koniec końców produkują one więcej dwutlenku węgla niż wyemitowałyby wszystkie auta z silnikami spalinowymi razem wzięte. To samo dotyczy zielonych, pasywnych domów – nie konsumują energii, ale buduje się je daleko od centrów miast. Ludzie, którzy w nich mieszkają, dojeżdżają codziennie samochodem do miasta zużywając olbrzymie ilości energii, niezależnie od tego, co napędza silniki ich samochodów.

Czyli polityka małych kroków i niewidzialna rewolucja w ogóle nie mają sensu?

Zmiany klimatu to poważny, narastający w skali globalnej problem, a mimo to panuje tendencja do rozwiązywania go przy pomocy zazwyczaj absurdalnie nieistotnych działań. Mamy więc zielone hummery, zieloną coca colę, zielone prezerwatywy, a tymczasem prognozy dla naszej planety są kiepskie. Zmierzamy ku apokalipsie.

Na konferencji klimatycznej COP24, która obradowała w grudniu w Katowicach, bryłki węgla posłużyły za element wystroju wnętrz.

Jakie to cyniczne. Niestety, chcąc być realistami, musimy być pesymistami. Chociaż trzeba zrobić wszystko, co w naszej mocy, żeby powstrzymać globalne ocieplenie, kopenhaski szczyt był porażką, ten w Kioto i paryski również, i wszystko wskazuje na to, że katowicki też okaże się porażką. Właśnie po raz pierwszy od wielu lat wyemitowaliśmy więcej dwutlenku węgla niż rok wcześniej. W mojej książce (polskie wydanie Four Walls and a Roof ma ukazać się niebawem nakładem Instytutu Architektury – przyp. aut.) jest rozdział pod tytułem Spaceship Earth – Statek Kosmiczny Ziemia. Otwiera go cytat z wywiadu z Buckminsterem Fullerem przeprowadzonego w 1972 roku przez redakcję „Playboya”. Fuller mówi: Czasem, gdy używam słowa „natura”, mam na myśli Boga. A przeprowadzający wywiad pyta: A czy kiedykolwiek mówisz Bóg, mając na myśli naturę?

Ale nie cytuje Pan odpowiedzi.

To prawda, bo nie odpowiedź jest interesująca, a sama zależność tych dwóch pojęć. Człowiek nie postrzega siebie w opozycji do natury, lecz jako całość i jedność z nią. W ujęciu religijnym jest ona nieodzownym bytem istniejącym poza człowiekiem. Za każdym razem, gdy próbujemy zadzierać z naturą, mści się na nas. Traktowanie katastrof naturalnych jako boskiej kary za ludzkie grzechy to typowo religijne podejście. Zadzierasz z Bogiem i spada na ciebie boski gniew. Widzisz się w opozycji do natury i jest ona ponownie Bogiem. Tymczasem człowiek to po prostu gatunek zwierzęcia, a zwierzęta są częścią natury. Tylko natura w ogóle nie jest już naturalna. Jej dziewiczość jest w dużej mierze fikcją. W Holandii mamy naturę, ale jest ona przekształcona ręką człowieka, nasz krajobraz naturalny jest równie nienaturalny, co architektura. Tak samo jest z rolnictwem, które mieszkańcy miast lubią idealizować. Tymczasem produkcja rolna to obecnie zaawansowane laboratoria, w których produkuje się modyfikowane genetycznie pomidory. Więcej innowacji jest dziś na wsi niż w uroczych miejskich farmach zakładanych na dachach. Wracając do Holandii – to sztuczny kraj. Gdyby nie Plan Delta (system tam i zapór wodnych w Holandii, jeden z siedmiu współczesnych cudów świata; jego realizację przyspieszyła wielka powódź z 1953 roku – przyp. red.), zwyczajnie by go nie było. System zapór i tam wodnych wymaga ciągłego utrzymywania. Wydajemy 1,3 miliarda euro rocznie, żeby nie znaleźć się pod wodą: na wiatraki, które osuszają poldery, na tamy, które trzeba stale umacniać, itd. Dla bogatej gospodarki 1,3 miliarda rocznie nie stanowi większego problemu. Jednak gdy temperatura wzrośnie o półtora stopnia – a to bardzo ostrożne prognozy, bo równie dobrze może podnieść się o dwa lub trzy stopnie – 1,3 miliarda już nie wystarczy. Przy wzroście temperatury o trzy stopnie, koszty będą tak wysokie, że nawet tak bogaty kraj, jak Holandia, sobie z nimi nie poradzi. Dlatego samo powstrzymanie globalnego ocieplenia, choć istotne, nie wystarczy. Musimy mieć plan co robić, gdy stanie się ono faktem. Prawdopodobnie Holandia będzie musiała całkowicie zmienić podejście do zasiedlania - będziemy mieszkać tam, gdzie woda nie dociera, a na terenach okresowo zalewanych rozmieszczać funkcje tymczasowe. Żyć razem z wodą i przemieszczać się razem z nią, zamiast budować fortece, by się przed nią chronić.

i

Wracając do nie dość odważnych i zdecydowanych działań, wspomniał Pan podczas jednego z wykładów, że skala takich przedsięwzięć jest odwrotnie proporcjonalna do świadomości problemu: im więcej wiemy o naszym negatywnym wpływie na klimat, tym bardziej nieistotne są podejmowane przez nas kroki.

Ten paradoks ilustruję zawsze wszystkimi wspomnianymi bezsensownymi i niewiele znaczącymi symbolicznie zielonymi akcjami.

Ale jeśli nie świadomość, to co?

Nie chodzi mi o deprecjonowanie świadomości tego problemu. Po prostu staram się pokazać, że najwidoczniej coś stoi na przeszkodzie wprowadzaniu prawdziwie efektywnych działań. Coś dopuszcza jedynie ten niekończący się katalog drobnych, symbolicznych poczynań, tak jakby zachowanie pozorów ekologiczności było ważniejsze od bycia naprawdę ekologicznym. Wszystko to jest niestety zakorzenione w naszym systemie ekonomicznym. Tak jak w Stanach Zjednoczonych, gdzie dużo mówi się o nierówności rasowej i molestowaniu kobiet, ale nikt nie jest gotowy przyznać, że te nierówności wyrastają z przyjętych zasad ekonomii. Kobieta molestowana w pracy jest molestowana dlatego, że może tę pracę stracić, a straciwszy ją, straci dom i ubezpieczenie zdrowotne. Kto w tej sytuacji zaryzykuje i poskarży się na szefa? W Davos można spotkać tych wszystkich rzekomo liberalnych Amerykanów rozmawiających o równości genderowej i tak dalej, ale to jedynie zasłona dymna, ponieważ żaden z nich nie jest gotowy do poważnej rozmowy o większej równości w dystrybucji dóbr. Pojęcie sustainability jest w bliski i nierozerwalny sposób związane z kwestią sprawiedliwości społecznej. Oszczędność, ograniczanie marnotrawstwa, dzielenie się, to wszystko się łączy. We wspomnianym wcześniej eseju Spaceship Earth nawiązuję do George’a Orwella. Orwell posługuje się metaforą małej łódki, w której jest tylko kilka rzeczy do podziału. To właśnie Ziemia – nasz statek kosmiczny z ograniczoną ilością zasobów do podziału.

Ani Pana, ani nasza generacja nie zebrała się na odwagę, by ogłosić w manifeście pomysł czy choćby wolę zmiany świata na lepsze. Jaki może być powód tak zachowawczych postaw?

Gospodarka rynkowa sprawiła, że wszystko stało się obiektem prywatyzacji i rywalizacji, a rywalizacja przeszkadza w udostępnianiu i szerzeniu wiedzy. Widać to zwłaszcza w dziedzinie medycyny – wyraźnie spadła liczba nowych patentów i publikacji przełomowych odkryć. Wszystko trzymane jest w tajemnicy, by wyprzedzić konkurencję. Jest różnica pomiędzy wyścigiem z konkurencją a postępem. Weźmy Donalda Trumpa i jego wojnę z Chinami: Musimy pokonać Chińczyków, żeby nasze było na wierzchu. To całe „my” i „oni” to nic innego jak regresywny samczy instynkt rywalizacji. Chrzanić zmiany klimatu, bo to chiński sabotaż wymierzony w amerykańską gospodarkę. Trump nie jest pierwszy i sam tego nie wymyślił. Jest tylko apoteozą takiego sposobu myślenia, produktem ubocznym mentalności permanentnego wzrostu i wiecznej konkurencji, która stanowi podstawę funkcjonowania całego społeczeństwa i gospodarki. Przypomnijmy sobie projekt globalnej sieci energetycznej autorstwa Fullera – kiedyś tylko nierealny, dziś całkowicie niemożliwy do zrealizowania.

I to nie z powodów technicznych, a politycznych.

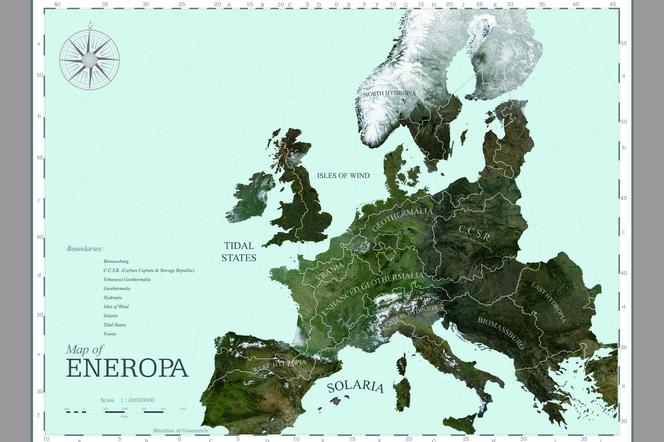

Wyłącznie z powodów politycznych. W naszym projekcie Roadmap 2050 (praktyczny przewodnik jak uczynić europejską gospodarkę niskoemisyjną powstał w 2012 roku z inicjatywy ECF – Europejskiej Fundacji na Rzecz Klimatu – przyp. red.) zastanawialiśmy się nad tym, co stałoby się, gdyby Europa była „sprytna” w kwestiach energetycznych. Na południu, gdzie jest dużo słońca, pozyskiwano by energię słoneczną, na północy, wliczając w to Holandię, gdzie mocniej wieje – wiatrową, etc. Każdy kraj odegrałby swoją rolę, a energią wymieniano by się poprzez sieci energetyczne. W takiej sytuacji – a udało się nam to udowodnić naukowo – nie tylko wystarczyłoby jej dla całej Europy, ale jeszcze wyprodukowano by nadwyżkę. Technicznie jest to możliwe, a mimo to nasz projekt nie zostanie zrealizowany i to nie z powodów ekonomicznych, a wyłącznie politycznych. Potrzeba by do tego naprawdę zjednoczonej Europy. Moglibyśmy wtedy pokazać środkowy palec Rosji i bogatym w ropę krajom Bliskiego Wschodu. Wygląda jednak na to, że zmiana kontekstu politycznego jest znacznie trudniejsza niż pokonywanie trudności natury technicznej.

Współpraca i współdziałanie nie są naszą mocną stroną, chociaż wszyscy jedziemy razem na tym samym wózku i pozornie wszyscy jesteśmy równi wobec konsekwencji zmian klimatu.

Właśnie – równi tylko pozornie, ponieważ ofiara, jaką każdy z nas będzie musiał złożyć, nie będzie taka sama. To nie jest tak, że nie ma porozumienia co do zmian klimatu – prawdopodobnie gdzieś w głębi serca nawet Trump wie, że są one realne. Ostatecznie wszyscy są zgodni, że coś z tym trzeba zrobić. Problem zaczyna się dopiero przy podziale kosztów. Konsekwencje zmian klimatu dotykają nas wszystkich, ale to, co musimy z tym zrobić w pierwszej kolejności, kto musi ponieść ofiary i jakie, to już zupełnie inna historia. Tu świat nie jest jednością.

W tej potencjalnie zerowej sumie cały czas jesteśmy pod kreską.

Tak, jesteśmy pod kreską, ale istotą ewolucji jest wyścig, w którym postęp technologiczny i związana z nim odpowiedzialność mają to samo tempo. Wraz z WWF pracowaliśmy nad projektem osiągnięcia w 2050 roku zerowej emisji w skali globalnej, jeszcze bardziej ambitnym niż wspomniana wcześniej Roadmap 2050. Cele zostały określone dwutorowo: maksymalizacja udziału energii ze źródeł odnawialnych i inwestycje w innowacyjne rozwiązania technologiczne przy równoczesnym ograniczeniu jej zużycia i zmianie pewnych przyzwyczajeń, dzięki czemu bilans zerowy udałoby się osiągnąć szybciej. Oczywiście, architektura musiałaby mieć w tym swój udział: trzeba by wykorzystywać naturalną wentylację, naturalne ogrzewanie, itd. Taką architekturę również realizujemy. Jednak, jeśli chodzi o rozwiązanie globalnego problemu, ona sama to zdecydowanie za mało. W tym kontekście nie można architektury traktować jako czegoś autonomicznego.

Dostrzega Pan jakieś wzorce lub ogólne zasady, których architekt powinien się trzymać?

Jest kilka prostych sposobów: są certyfikaty energetyczne, są rozwiązania, za sprawą których te idealne dla człowieka 21,5 stopnia Celsjusza można osiągnąć w naturalny sposób, a nie przy pomocy klimatyzacji. Nie brakuje pomysłowych realizacji w historii, wliczając w to architekturę modernistyczną. Jednak są takie miejsca na świecie, gdzie myślenie o tym, co może wydarzyć się za dwadzieścia lat, jest luksusem, ponieważ trzeba martwić się o tu i teraz. Nawet w bogatszych regionach, gdzie ludzie mogliby sobie pozwolić na bardziej dalekowzroczne myślenie, wygrywa instynkt krótkowzroczności.

Zwłaszcza wśród inwestorów i deweloperów.

Zwłaszcza wśród inwestorów i deweloperów. Wielokrotnie zdarzało się nam powtarzać klientom, że wcale nie potrzebują budynku, albo nawet, że nie potrzebują projektu. Na przykład Bruksela chciała stworzyć nową stolicę Europy. Powiedzieliśmy im, że to, jak miasto wygląda, to akurat najmniejszy problem. Korzystniejsze finansowo byłoby dla nas zaprojektowanie tych budynków. Zdarza się, że jesteśmy oskarżani o bycie częścią globalnej gospodarki opartej na architekturze, jednak przez te wszystkie lata często podejmowaliśmy decyzje, które nie zgadzały się z rachunkiem ekonomicznym. Jesteśmy dużą i wpływową pracownią architektoniczną, ale nie jesteśmy bogaci. Gdybyśmy pewne decyzje podjęli inaczej, nasz majątek byłby znacząco większy, ale zysk nigdy nie był dla nas najważniejszy.

A co jest najważniejsze w takiej zorientowanej na badania pracowni jak AMO?

Ciekawość. Ciekawość tego, co oprócz architektury i poza nią.

AMO to był oddolny pomysł architektów z biura OMA?

Nie wiem – oddolny czy odgórny. Ciężko mi stwierdzić, czy w firmie znajdowałem się wtedy na górze, czy na dole. Nie ma to chyba większego znaczenia. Po prostu postanowiliśmy coś takiego zrobić. Chcieliśmy wiedzieć więcej. Gdy wie się więcej, można zacząć układać plan i ustalać, co chce się zrobić. Najważniejsze było uświadomienie sobie, że architektura niewiele w tym wszystkim miała do zaoferowania. Sporo decyzji wydawało się arbitralnych. Ostatecznie, gdy ktoś przychodzi do architekta z problemem, architekt ma jedną odpowiedź: budynek. Dlaczego? Dla zysku. Rozwijając wiedzę z różnych dziedzin, jesteśmy w stanie zaoferować ludziom strategiczne doradztwo, obejmujące szersze pole i nieobciążone żadnymi ukrytymi motywami.

Dlaczego właśnie zmiany klimatu? Jak to się stało, że akurat ten temat stał się osią waszych badań?

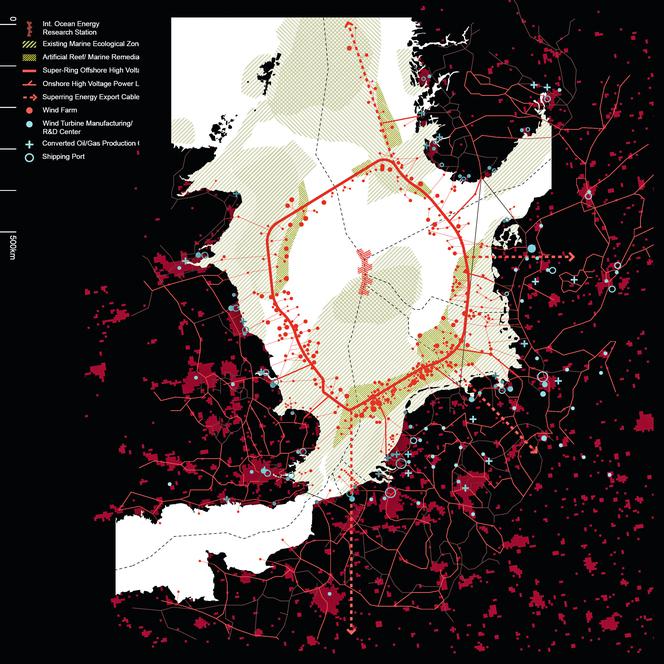

Wszystko zaczęło się od masterplanu dla Morza Północnego, o który poprosiła nas pewna organizacja pozarządowa. Brzmiało to niezwykle interesująco – robiliśmy wcześniej masterplany, ale zawsze dla obszarów na lądzie. Temat nas zaciekawił i tak się zaczęło. W badaniach naukowych najważniejsze to nie wiedzieć, dokąd się zmierza, nie zakładać z góry celu, jaki chce się osiągnąć. Gdy się je prowadzi, nic nie jest pewne, każde nowe odkrycie sprawia, że definiujesz podejście na nowo. Najważniejsza jest ciekawość i gotowość zaakceptowania jej konsekwencji, tego, dokąd cię zaprowadzi nawet jeżeli trzeba będzie zmienić obrany wcześniej kierunek. Jestem pewien, że wiele rzeczy zrobiliśmy nie tak jak trzeba.

Na pewno nie flagę europejską w 2004 roku, to był bardzo pomysłowy projekt.

Nie wiedzieliśmy, w którą stronę pójdzie Unia Europejska, więc chcieliśmy, żeby flaga mogła „rosnąć” wraz z nią. Niestety okazało się, że flaga, która może rosnąć, może się również kurczyć.

i

Reinier de Graaf, holenderski architekt, partner w pracowni OMA i współtwórca działającego w jej ramach think tanku AMO. Wykładowca University of Cambridge. Autor książki Four Walls and a Roof. The Complex Nature of Simple Profession (Harvard University Press 2017), uznanej przez „Financial Times” i „Guardian” za najlepsze wydawnictwo o architekturze roku 2017. Rozmowa odbyła się przy okazji wykładu Architektura bez właściwości (Architecture without Qualities) zorganizowanego 6 grudnia 2018 roku w Krakowie przez fundację Instytut Architektury i Goethe-Institut Krakau w ramach cyklu Elementy Architektury 2018

You’ve mentioned that buildings are among the most important assets in global economy, often built for money rather than to be dwelled in. At the same time, as recent research by climateco.lab revealed, buildings are responsible for as much as 38%, and residential buildings for as much as 20%, of all human GHG emissions.

It is not architecture but people who are responsible for the emissions. Buildings are ‘responsible’ for the large part of the emission because this is where people spend the majority of their time.

But is there a chance for architecture to become again a means for survival and adapting to climate change, instead of only making things worse?

This is part of a larger question. One of the key things is that all things that go well are invariably at the expense of something or somebody else. Certain countries, for instance, have the ecological footprint 5, 10, 100 times their surface. We are but too slowly coming to realise that the price of certain successes are failures and limitations upon others. Isn’t it interesting that the issue of sustainability emerged when the world – economically – tended to be one? For the first time in history we can do the zero sums with pluses on one side and minuses on the others. Previously the two parts were completely separated and the pluses could never solve the minuses. This is exactly the case of architecture. This is why it seems important to me to talk about architecture in terms of an element in a cycle, rather than a culprit.

Speaking of cycles, part of your research is focused on ephemeral buildings. What’s the essence of their phenomenon?

The shorter buildings live, the more you are forced to consider them part of the cycle. When you plan their construction in terms of their demolition, the prime element is not their creation, but their disappearance. On the other hand, the longer buildings exist, the more we regard them as inevitable monuments on their own.

Brevitas, flexibilitas, humilitas instead of firmitas, utilitas, venustas?

Precisely. Durability and sustainability are not about being eternal. Sustainable planning is about planning how you go when you go. Buildings, in this context, are not interesting at all. The more I practice architecture, the less I become interested in buildings on their own, as autonomous masterpieces. It is more about the role they play within a larger system. Buildings are parts of a post-industrial society that produces and consumes, that has a certain way of manufacturing things.

i

In the case of the new town hall in Rotterdam demolition strategy gave you some extra BREEAM scores.

It was pure luck. We didn’t want to cut the costs on the quality of the building but, since we had to cut some costs, what we reduced was the building time, since in the Netherlands labour is more expensive than material. We did a prefabricated building that could be built in no time. We could do big cantilevers, generous spaces, a rich facade, outdoor terraces, etc., all because of prefabrication. And a building that can be erected quickly, can be also quickly demolished. The latter gave us the biggest plus on the whole BREEAM list. It’s like the real resilience, or the real sustainability, would be to not build at all.

Do you prefer sustainability or resilience?

Neither. Any word that is too frequently used becomes an awful cliché. If I had to choose, I’d prefer sustainability, but I tend to avoid both.

But resilience is more flexible by definition, operating outside the category of lasting and eternal, isn’t it?

At the same time, it has this notion of being resilient against the elements, of existing no matter what. I have a problem with the word sustainability, resilience, etc. They tell you what to do without promising anything in return. They all are too evangelical to me, too protestant, too catholic, too little scientific. They are all not atheist enough.

Which of the fancy words do you prefer?

Adaptability. I find it the least offensive.

How about sharing? Like in the case of the People’s Pavilion designed for Dutch Design Week 2017, built of borrowed materials found around the site?

It’s cute and perfect but think of the size of the problem! You have a house on fire and the neighbour comes with a kettle of water. The intention is good but there is a distinction between what is morally good and what is effective. They are hardly ever the same.

Do you prefer effective solutions?

I always have a problem with any discussion that is too overborn with moralism, and the whole sustainability debate, and a lot of the resilience debate, is quite moralistic. In the Netherlands we have a big promotion of electric cars. But while the government is promoting electric cars because they are zero-emission, they are building coal plants in order to provide power for charging batteries because coal plants are cheaper. They eventually emit more CO2 than all the diesel and petrol cars would have emitted altogether. There are green houses that are energy neutral but they are located miles away from city centres and the people who live in those green houses commute by car, consuming massive amounts of electricity or petrol every day.

No small steps and the invisible revolution whatsoever?

Climate change is a global problem but there is a curious tendency to solve this large, globally-escalated problem with interventions that on average are ridiculously small. We have green Hummers, green Coke cans, green condoms, while predictions for the Earth are quite apocalyptic.

There is the COP24 Climate Change Conference being held in Katowice as we speak where lumps of coal are used as decoration.

So cynical. It’s probably realistic to be pessimistic about this. We have to do everything to limit global warming and, still, Copenhagen was a failure, Kyoto was a failure, Paris was a failure and Katowice is about to be a failure. I read today that for the first time in years we emitted more CO2 than the year before. There’s a chapter in my book Four Walls and a Roof, titled Spaceship Earth. It starts with a quote from R. Buckminster Fuller, interviewed by Playboy in 1972, who says: When I use the word nature, I sometimes mean God. And the interviewer askes: Do you ever say God and mean Nature?

But the answer is not quoted.

True, but it is the reciprocity that is interesting. The man doesn’t see himself as an opposition to nature but as a whole with nature. There is this religious view of nature where you see nature as an inevitable entity outside man, and whenever you mess with it, nature takes revenge. It is very religious a view to see natural catastrophes as God’s punishment upon bad human behaviour. Then you see yourself in opposition to nature and nature is, again, God. And if you mess with God, the God’s thorn comes upon you. There’s another thing: Man is just another species of animals and animals are part of nature. But nature is already artificial, and authenticity of nature is very much a fiction. In the Netherlands, there is mud, there is clay, there is grass, but it is all man-made. The countryside is as artificial as architecture. The urban dweller romanticises farming to an unhealthy degree, while the countryside is a hardcore laboratory of genetically modified tomatoes. There is more scientific innovation in the countryside than in the city with all the urban farming on cute little roof tops. The Netherlands is an artificial country. If it weren’t for the dikes and all the engineering works, our country would simply not exist. These are not one-time interventions; they require permanent maintenance. Our country spends 1,3 billion Euro every year to make sure it doesn’t go under water, on mills that keep the polders dry, on dikes that are reinforced every year, etc. For a rich economy, 1,3 billion a year is doable. But when the temperature rises by 1,5 degree – and this is very conservative of an estimate, it can be 2 or 3 degrees – 1,3 billion a year will not be enough. At 3 degrees, even a country as rich as the Netherlands will not be able to afford it. I think it is important to limit global warming, but it won’t be enough. We need strategies for when it happens. In the Netherlands, we need to rethink our settlements, to live in the parts that never flood and allow certain parts to be flooded (have some temporary uses there), to live with the water and move with the water, rather than build fortresses to protect ourselves from it.

Some years ago, in 2010, you said during one of your lectures that the scale of action is reversibly proportional to the level of awareness: the more we know about our negative influence on climate, the less meaningful actions are being undertaken.

It is a paradox I illustrate with all the meaningless and minute green symbolic actions.

But if not awareness then what?

It is not about undoing the awareness. It is simply to illustrate that apparently something stands in the way of efficient actions, something that allows only the endless range of small symbolic actions, as if to be seen green is more important than to actually be green. It is all rooted in our economic system. In the United States, for instance, there are massive movements against harassment of women and racial inequality but nobody is prepared to acknowledge that inequality is rooted in the economic system. Women who get harassed at work can only be harassed at work because they can be fired, and when they get fired, they lose their health insurance, they lose their home. So, who is going to complain about their boss when that is the risk they face? At Davos, you see all the supposedly liberal Americans talking about gender equality, etc. It is but a smoke screen to the fact that nobody is ready to reconsider the way wealth is distributed. In that essay, Spaceship Earth, I make a link that George Orwell made: The issue of sustainability is closely and ultimately related to social justice. Not being wasteful, saving, sharing are reciprocal. Orwell uses the metaphor of a little boat where there are only few things to be shared. This is the spaceship Earth: a spaceship with a limited amount of resources.

Why neither our nor your generation has been courageous enough to write a manifesto advocating an idea or at least a will to change the world for the better? What’s the reason of such conservative attitudes?

It is the market economy that has made everything subject to privatisation and competition. And competition prevents the sharing of knowledge. Particularly in the field of medical research the number of patents applied for and successful breakthroughs dropped significantly. It is all about beating the others. But there is a difference between beating your competitor and achieving progress. There is a huge difference between winning and succeeding. Take Trump for instance, as he goes to war with China: It is important that we beat the Chinese, so we win. The whole we and them is a retrograde competitive male instinct. Let’s fuck climate change because climate change is a Chinese invention to sabotage the American economy. However, it is a way of thinking that did not start with Trump. Trump is in many ways an apotheosis of this way of thinking, a by-product of a way of thinking that has become the norm. It is a mentality upon which the whole society and economy are organized: growth and competition. Take Fuller’s project of the global energy grid, for instance – unrealistic back then, impossible now.

Not for technical but for political reasons.

Purely for political reasons. In our Roadmap 2050 project we wondered what would happen if Europe was smart about energy: the South would use solar energy, the North, including the Netherlands, would use wind energy, etc. There would be a degree of role-play between the nations and a proper exchange through energy networks. If that were the case – and it was scientifically proved – there would be plenty of renewable energy for everyone in Europe and more. Saving energy would not be even necessary. It is technically possible, but the reason why it doesn’t happen is political, not economic. It would be possible if there were a united Europe. We could tell Russia to fuck off, we could tell the oil-rich Middle Eastern countries to fuck off, etc. To change the political context appears to be much more difficult than to surpass technical difficulties.

Coming together doesn’t seem to be the strongest of our points. It seems that we are all equal when it comes to face the consequences of climate change and air pollution, and yet…

Because the sacrifices that we all have to make are very different. It is not that there is disagreement on climate change. Probably deep down also Trump knows that climate change is real. Let’s say that there is no real dissensus on whether climate change is real or that something ought to be done about it. The whole problem starts once the sacrifices have to be divided. We are all equally affected by climate change but in the short-term what we have to do about it, who has to make the sacrifices and what sacrifices, are a very different story and that is where the world is not one at all.

If we compare our inputs and outputs, we are on the wrong side of the clock.

Yes, we are on the wrong side, but in its essence the evolution of the Earth and of Man is a neck and neck race between technological inventions and responsibility. We worked with the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) on a project about a zero-emission world in 2050, far more ambitious than the Roadmap 2050. It had a two-track objective: maximise revenue from sustainable energy sources and simultaneously cut energy consumption, so the desired balance comes sooner. On the one hand, there would be aggressive investment in technological innovation and on the other hand, the moderation of behaviour. Of course, architecture should do its part, too: use natural ventilation, natural heating, so on and so forth. We produce that kind of architecture, too. But in terms of solving the global problem, architecture will never do it alone. In this context architecture can’t be considered autonomous.

In this context, do you see any patterns or general rules to be applied in architectural design?

There are energy norms. There are clever ways to design buildings where the ideal of 21.5 degrees Celsius for a human being is achieved in natural ways rather using air-conditioning. There is often cleverness in the tradition of architecture – modern architecture included – but there are also parts of the world where thinking on what may happen in twenty years is more like a luxury, for their concerns are more immediate. Even in the wealthy parts of the world where people can afford to think on the long term, human beings have this instinct to be short-sighted.

Even investors.

Especially investors. We have often told investors they didn’t need a building at all. When Prada first came to us, we told them they didn’t need a building. Or the City of Brussels. They wanted an urban design for Brussels as the capital of Europe and we said: No, you have an entirely different problem. The way the city looks like is the least of your problems. Financially, we would have done a lot better if we had just designed buildings. We are sometimes accused of being part of the global architectural economy but over the years we have taken plenty of business decisions that went against our own wallet. As a practice, we are big, we are influential, but we are not rich. If we had done some things differently, we could have been way richer, but profit maximizing is not a central value of our company.

What is a central value of a research-oriented architectural practice like AMO?

Curiosity. Of what is beside and beyond architecture.

Was it a bottom-up idea of OMA’s architects?

I don’t know. We have just decided to do it. I don’t know whether I was on the bottom or on the top of the organisation at that time, but it is not so important. It was simply a desire to know more. When you know more, then you can start developing agendas, you can start developing what you want to do. But the most important thing was to realise that architecture provided little explanation for things from within. Many decisions we felt were arbitrary. As an architect, when someone comes to you with their problems, you say: You need a building. Why do you say this? For your own profit. By developing knowledge in different fields and domains we are able to give strategic advice to people on a wider level, advice that is unburdened by ulterior motifs.

When or how the issue of climate change becomes subject of your research?

We started researching climate change when an NGO asked us to do a masterplan for the North Sea. It was an interesting project because we used to make masterplans but we always made them for land. It was unusual. It made us curious and one thought led to another. The essence of research is that you do not define the goal in advance because nothing is certain when you do research and everything you find leads to the readjustment of your goals. Curiosity makes the difference, as well as accepting the consequences of your curiosity, even if that means changing the direction that you’ve taken. There is a huge number of U-turns and the whole oeuvre is utterly inconsistent. I’m sure we do a lot of things wrongly.

Not the European flag from 2004, that was quite a witty design.

We designed it to be expandable for we didn’t know which way the EU would go. Unfortunately, the flag appears to be shrinkable as well.